Short-term rental applications, such as Airbnb, have revolutionized the real estate market and tourism sector. By acting as an intermediary, the application offers peer-to-peer accommodation for a short period, growing exponentially. However, tout n’est pas rose dans la vie. Airbnb business model became a source of concern both for the traditional tourism accommodation sector and the real estate market of destinations. Labelled as a “disruptive innovation”, Airbnb has helped to construct an informal tourism accommodation sector which has impacted many cities. Lisbon is a good example of Airbnb’s impact, in a movement to renovate buildings, the Portuguese national rental law was modified, facilitating evictions and boosting the short holiday rentals market.

Looking at this problem, the European Commission has adopted a Proposal for a Regulation to enhance transparency in short-term accommodation rentals. With the objective of helping public authorities to ensure balance in a developing tourism sector, the Proposal aims to create a data-sharing framework between hosts and platforms to inform effective and proportionate local policies. Furthermore, reducing bureaucracy for hosts, impacting the market and facilitating the development of urban planning plans through data harmonization. Thus, the Proposal fits into the already existing policy provisions, such as GDPR, Digital Services Act, e-Commerce Directive, Platform to Business Regulation, and Data Act Proposal.

Hereinafter, I will focus this blog post on a few aspects of the Proposal which are connected to data protection, data sharing and data portability.

In an effort to create a harmonized database, Article 5 (b) sets that where hosts are natural persons, they must submit their name, national identification number, or any other identification information, address, telephone number, and mail address in order to insert their rental on the platform. Member States may require that the information provided is accompanied by supporting documents, however, it leaves it to the Member States to further regulate the format of this documentation. Article 5 (5) defines that Member States must ensure that the information and documentation submitted are retained in “a secure and confidential manner and only for a period which is necessary for the identification of the unit”, establishing the data can only be kept up until 1 year after the host’s request to remove the unit from the application’s registry.

Another very interesting section of the Proposal is the second part of Article 5 (5), which mentions that the Member States must ensure the documentation is “only used to ensure compliance with the applicable rules of the Member State concerning access to and provision of short-term accommodation rental services”. This statement opens the door to a myriad of suppositions: would it be possible to process this data for tax purposes related to short-term accommodation rental services? Article 12 of the Proposal seems to answer yes, by setting that access to information shall be granted to the competent authority responsible for “implementing rules governing the access to and the provision of short-term accommodation rental services”.

Lime e-scooter red zone example

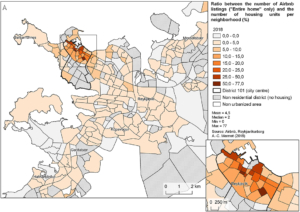

When it comes to urban planning and public policy, Article 7 establishes that platforms must design and organize their interface in a way that makes it possible for hosts to self-declare where the rental service is located. This determination is a big step towards the regulation of the short-term rental market by the Public Sector, allowing the creation of a “short-term services map”, with “red zones” areas in which short-term rentals are forbidden similar to the ones implemented by e-scooters.

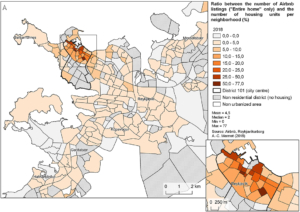

Ratio between the number of listings and the number of residences per neighborhood in the Reykjavík Capital Area.

Article 12 (3) (a) and (b) emphasizes that anonymized activity data might be shared with other public authorities tasked with developing laws, regulations and administrative provisions concerning access to and provision of short-term accommodation. This data can also be shared with entities and persons who carry out scientific research, analytical activities or develop new business models. Therefore, the Proposal removes power from platforms, giving the Public Sector the possibility to further share this data for research purposes.

Chapter III, related to “Data Reporting” creates an obligation for online platforms to share activity data and registration numbers on a monthly basis with Member States. Each Member State will create a “Single Digital Entry Point”, which will be the data entry point for the receipt and forwarding of activity data (Article 10). Each Member State will designate an authority responsible for the operation of the Single Digital Entry Point.

Article 10 also lays out a series of technical considerations related to the Single Digital Entry Point which evolves data portability. It regulates that Member States must provide a technical interface which enables platforms to provide machine-to-machine and manual transmission of activity data to the Digital Entry Points. They also must facilitate checks by platforms and competent authorities and guarantee data interoperability between the Single Digital Entry Point and with State’s documental registries for check purposes. Digital Entry Points also must guarantee data re-use, if the same information or documentation is requested by multiple registries within the same Member State.

Thus, although this is the first version of this Proposal, this future Regulation will be an interesting step forward in many aspects which include data protection, data sharing, data portability and urban public policies.

Unlike ordinary trading objects, data has both basic use value “information collection” (eliminating the information asymmetry between the parties in the transaction) and potential use value “data analysis and prediction”. Personal data have little use value for information producers but have exchange value for other parties in the transaction to achieve information symmetry or expand the advantages of information asymmetry. Other available data in the market have basic use value for individual users to obtain information, but it is difficult to generate exchange value through individual collection or analysis because of its openness and accessibility. The company or platform can realize both the basic value and the potential value through data aggregation, data fusion, etc.

Unlike ordinary trading objects, data has both basic use value “information collection” (eliminating the information asymmetry between the parties in the transaction) and potential use value “data analysis and prediction”. Personal data have little use value for information producers but have exchange value for other parties in the transaction to achieve information symmetry or expand the advantages of information asymmetry. Other available data in the market have basic use value for individual users to obtain information, but it is difficult to generate exchange value through individual collection or analysis because of its openness and accessibility. The company or platform can realize both the basic value and the potential value through data aggregation, data fusion, etc.

The program had three parts and the first part started with two presentations from professionals who working on health data. The first presentation was given by Katharina Lauer from COVID-19 Data Portal by the ELIXIR project. In her presentation, we received insights about challenges they faced during the pandemic, for instance, lack of standardization and different interpretation of law across data-sharing infrastructures. The second presentation was given by Nikolas Molyndris from Decentriq which is a newly founded company to enable secure data connections between different partners by using privacy-enhancing technologies such as confidential computing and federated learning.

The program had three parts and the first part started with two presentations from professionals who working on health data. The first presentation was given by Katharina Lauer from COVID-19 Data Portal by the ELIXIR project. In her presentation, we received insights about challenges they faced during the pandemic, for instance, lack of standardization and different interpretation of law across data-sharing infrastructures. The second presentation was given by Nikolas Molyndris from Decentriq which is a newly founded company to enable secure data connections between different partners by using privacy-enhancing technologies such as confidential computing and federated learning. In this sense, being discriminated against while receiving health services will also have a secondary effect. She also talked about this concept, which she defines as data injustice, and that we need to make efforts to reduce this effect. Katharina Lauer remarked on the different layers of health data and a novel area called ‘planetary health’ which we will be hearing more about in the future as a result of climate change and migrations due to these changes. Elizabeth J. Davidson referred that health data is integrated into every part of human existence and thus has enormous importance. In this regard, while technology is advancing and sharing data is getting easier day by day, hesitations around sharing must be evaluated carefully. Daniel Fürstenau flagged up the inconstant nature of health data and this feature must not be disregarded while collecting and processing health data.

In this sense, being discriminated against while receiving health services will also have a secondary effect. She also talked about this concept, which she defines as data injustice, and that we need to make efforts to reduce this effect. Katharina Lauer remarked on the different layers of health data and a novel area called ‘planetary health’ which we will be hearing more about in the future as a result of climate change and migrations due to these changes. Elizabeth J. Davidson referred that health data is integrated into every part of human existence and thus has enormous importance. In this regard, while technology is advancing and sharing data is getting easier day by day, hesitations around sharing must be evaluated carefully. Daniel Fürstenau flagged up the inconstant nature of health data and this feature must not be disregarded while collecting and processing health data.

Aizhan presented her topic “Data privacy and data trust – how to find a balance”, in which she raised the issue to find the best way to comply with the principle of where data is “as open as possible, as closed as necessary”.

Aizhan presented her topic “Data privacy and data trust – how to find a balance”, in which she raised the issue to find the best way to comply with the principle of where data is “as open as possible, as closed as necessary”. the point of view of comparing the political spaces of Poland and Kazakhstan according to such criteria as the legal framework, information awareness of citizens of both countries and digital capabilities in the political space.

the point of view of comparing the political spaces of Poland and Kazakhstan according to such criteria as the legal framework, information awareness of citizens of both countries and digital capabilities in the political space.